The felix culpa:

The Unfortunate Nature of the Fortunate Fall and Its Ties to Obedience

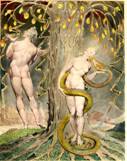

John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, discusses the Fall of humankind from Paradise. The Fall

occurs when Adam and Eve, after tempted by Satan, eat the fruit of the Tree of

Knowledge. In doing so, Adam and Eve

show disobedience towards God and are, subsequently, expelled from Eden, or Paradise. The Fall described in the poem is often

referred to as a felix culpa, or

fortunate fall, meaning that although the expulsion is the direct result of

sin, the outcome of the Fall is essentially for the good of humankind. However, the Fall of humankind is not, in

fact, fortunate, for it does not create a better existence for humankind than

that which humankind enjoyed before the Fall.

Nor does the Fall benefit the majority of humans or provide humankind

with greater knowledge of God’s mercy.

This illustrates the idea that the Fall does not occur to ultimately

benefit humankind, but rather to display the necessity of humankind’s obedience

to God.

In John Milton’s poem, Paradise

Lost, he presents the story of humankind’s fall from Paradise. In the poem, Adam and Eve cause the Fall to

occur by eating the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge and, subsequently, by

disobeying the wishes of God. Through

his poem, many see the Fall as an essentially positive event, calling it a felix culpa, or fortunate fall. The felix

culpa idea suggests that the Fall of humankind was necessary in order to

allow for a greater good to occur. This

is to say that without the Fall, the salvation of humankind through the

sacrifice and resurrection of Christ would not have occurred and it is because

of this event that humankind is able to experience a higher sense of

happiness. Although humankind becomes

exposed to sin and death after they fall from Paradise,

they are also given the opportunity to experience the mercy and love of God

through their reestablished obedience towards Him. In other words, while God punishes those who

sin, those who remain obedient to Him are rewarded with salvation. Subsequently, many argue that the Fall of

humankind is indeed fortunate, for if this fall had not occurred, they feel humankind

would not have been given the opportunity to feel the true extent of God’s mercy

and love.

Although many consider humankind’s fall from Paradise to be fortunate, or a felix culpa, this view is dependant on what humankind’s situation

after the Fall is being compared to.

Those who believe that the Fall is ultimately fortunate seem to be

comparing the post-fall existence of humankind to Adam and Eve’s existence

directly after the Fall and not to

their existence pre-fall. When this is

done, it is easy to find the positive nature of the Fall: humankind has been

offered a chance at salvation rather than a life of eternal damnation. The archangel Michael says, “To leave this Paradise, but shalt possess / a paradise within thee

happier far”. Even Adam remarks:

O goodness infinite, goodness immense!

That all this good of evil shall produce,

And evil turn to good; more wonderful

Than that which by creation first brought forth

Light out of darkness! full of doubt I stand,

Whether I should repent now of sin

By me done and occasioned, or rejoice

Much more, that much more good thereof shall spring.

Here,

Adam displays his happiness over the prospect of humankind’s possible

salvation. However, Adam makes the

comparison between this prospective existence and his current existence, not to

his existence in Paradise before the Fall. When comparing

Adam and Eve’s existence pre-fall, the outlook does not seem as fortunate. In fact, although Adam is happy about the

prospect of salvation, given his current state, even he is hesitant in

describing the Fall as completely fortunate.

Adam is “full of doubt”

as to whether or not the Fall is truly fortunate. Adam’s happiness is the result of the fact

that he is looking forward at what he has to gain after he has fallen, as

opposed to looking back and examining what he once possessed, before the Fall. As John C. Ulreich, Jr. puts it:

It is quite reasonable to say that the good resulting from

the Fall far outweighs ‘all our woe,’ that the Incarnation completely

overbalances the consequences of original sin…But it is not reasonable to

suppose that the benefit will be greater than it could otherwise have been.

So, for

Adam and Eve, who are in a state of despair after the Fall, any improvement on

their state of being would be seen as something positive. However, to compare the sin of humankind to

the new prospect of salvation is not appropriate. One must compare the new state of humankind

to the state of humankind before the Fall.

Only when this is done can a true comparison be made. This illustrates that the post-fall existence

of humankind is more bleak than the pre-fall existence and that the Fall of

humankind is not fortunate.

The vision of humankind’s future

existence that Michael provides to Adam in Book XII allows one to recognize

that this post-fall existence is less beneficial than the existence that Adam

and Eve enjoyed in Paradise before the Fall.

William G. Madsen refers to this vision: “Indeed, there is very little to

rejoice at in Michael’s previous account of human sinfulness. In effect, all that he has said is that a few

men will regain the happiness that Adam lost, and that the far greater part of

mankind will suffer eternal damnation in Hell”. Those who obey God and are devoted to Him

will receive mercy and salvation.

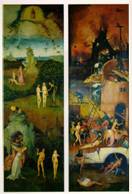

However, far more will be forced to suffer for their sins and for the

sins of humankind: “To judge the unfaithful dead, but to reward / His faithful,

and receive them into bliss”. However, this is not an improvement on Adam

and Eve’s original place in Paradise. In Paradise,

all are granted happiness, not just a select few. So, it does not seem fortunate to diminish

the number of humans who are able to experience this happiness: “If all could

originally have remained saved, why damn them in order to save only a

few?...Even the supposititious greater happiness of those few fit survivors

could never be held to justify such waste”. Walter G. Madsen also comments on this idea:

“It does not seem that much more good has sprung from Adam’s sin if all that

God can succeed in doing is salvage one or two men in every age and restore

them to the blissful seat that all men would have enjoyed had Adam remained

obedient”. So, although the Fall may turn out to be

fortunate for a select few, a far greater amount of people are forced to live a

life of eternal damnation. The Fall as a

whole cannot be considered fortunate as it is unfortunate for a greater amount

of people.

Often times, the Fall is thought to be fortunate because it

allows humankind to realize the mercy and love of God. However, this causes the Fall to appear unnecessary,

for Adam and Eve are already aware of God’s providence towards them before the

Fall occurs. The Fall provides no

further revelations in regards to this.

Hugh White notes:

It might be that they come to know, on surer evidence than

they had before they fell, the enormous depth and reach of God's goodness, but

since they knew already that God is all-loving and all-powerful, the force of

the Fall here is only really to give occasion for an essentially redundant

demonstration: there has never been any doubt that God's goodness is infinite

and immense, and it should be no surprise to find testimony of this….

So, if

after the Fall, Adam and Eve are made aware of God’s grace, it is a mere

confirmation of the awareness that they already possess. This ‘new’ knowledge is not, in fact,

providing any new information, but rather stands to regurgitate the knowledge

that Adam and Eve have possessed from the beginning. This, therefore, refutes the idea of the Fall

being productive and, consequently, that the Fall is a fortunate occurrence for

humankind.

The fact that the Fall is,

ultimately, unfortunate for humankind ties into the need for humankind’s

obedience to God. While many, including

God, try to justify the Fall by classifying it as fortunate, it remains nothing

more than a further test of humankind’s obedience to God. Throughout his poem, Milton stresses the idea of obedience. In fact, the entire poem is, “Of man’s first

disobedience…”. The Fall is used as a tool to illustrate the

importance of remaining obedient to God.

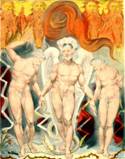

While Satan stands to show what will happen to those who do not obey God

after a fall, Adam and Eve stand to show what happens to those who do. Adam and Eve, in essence, contrast the

actions of Satan. After Satan is

expelled from Heaven, he continues his disobedience to God and goes as far as

leading a revolt against him. The

consequence of Satan’s actions is that he must face eternal damnation in

Hell. Contrastingly, upon their fall, Adam

and Eve express their renewed devotion to God.

They promise to once again obey God and, subsequently, are able to work

towards salvation. In this way, the Fall

of humankind is used as a tool to contrast the consequences of those who remain

obedient to God and those who do not.

The epic poem, Paradise

Lost, by John Milton describes the temptation of humankind and their

eventual fall from Paradise. In the poem, Milton portrays this fall as being

fundamentally fortunate, or a felix culpa. However, the Fall does not end up benefiting

mankind, as some would argue. This is

due to the fact that the Fall does not offer a better existence for humankind

when compared to the existence that humankind experiences before the Fall occurrs. Furthermore, the Fall does not provide a

positive outcome for the majority of humankind, nor does it heighten the

knowledge of humankind in terms of understanding the mercy of God. Subsequently, the Fall cannot be seen as

benefiting humankind, or being a felix

culpa, but rather serves as an example of the importance of staying

obedient towards God.

Bibliography

Duncan,

Joseph E. “Paradise as the Whole Earth.” Journal of the History of Ideas 30.2

(1969): 171-186.

Lovejoy,

Arthur O. “Milton

and the Paradox of the Fortunate Fall.” ELH

4.3 (1937): 161-179.

Madsen,

William G. “The Fortunate Fall in Paradise

Lost.” Modern Language Notes 74.2

(1959): 103-105.

Milton,

John. “Paradise Lost.” The Major Works

including Paradise Lost. Eds. Stephen Orgel and Jonathan Goldberg. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1991.

355-618.

Ulreich,

Jr., John C. “A Paradise Within: The Fortunate Fall in Paradise

Lost.” Journal of the History of Ideas

32.3 (1971): 351-366.

White,

Hugh. “Langland, Milton,

and the felix culpa.” The Review of English Studies 45.179

(1994) : 17 March 2006 < http://www.geocities.com/magdamun/white.html>.